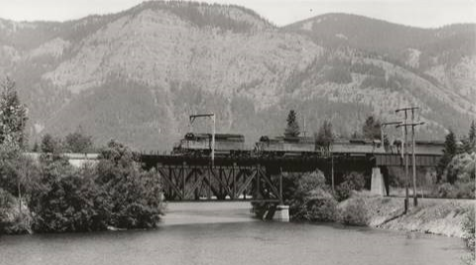

A week ago (preceding page), I stumbled portraying the closeness of the Milwaukee Road to the Northern Pacific Railway trackage. The two pictures here are the same location as last week’s Northern Pacific eastbound North Coast Limited, just nosing under the bridge. In both pictures above, the Milwaukee freights are westbound. The tunnel where #22 is exiting is about two car lengths behind the four diesels. If you were to Google-Earth this location you would see the valley is quite constricted here. The river is flowing away from the photographer.

The four diesels are crossing the Yakima River, but will only remain on that side for about a mile. The Milwaukee line continues up the Yakima River Valley, ducks into a short tunnel, follows the shoreline of Lake Keechelus, enters two snow sheds before the 11,789-foot Snoqualmie Pass tunnel. Both railroads enjoy relatively level travel up the valley, the Milwaukee all the way to the long tunnel. Northern Pacific trackage climbs a 2.2 percent grade from just behind the cameraman for about six miles to their Stampede Pass Tunnel.

The NP and Milwaukee do chase each other at various locations in the states of Washington and Montana. They are within sight of each other from the scene in these pictures, Lake Easton to Ellensburg, most of 40 miles. In western Montana for many miles along the Clarks Fork River they are much like double-track in some places, and zip in and out-of-sight for about a hundred miles. They share sides of the Yellowstone River in eastern Montana for about 85 miles.

Picture credits: diesels on bridge by Robert W. Johnston; #22 at tunnel by Dale Sanders